In a Classroom Minutes from Washington, D.C., Children Already Fear the Government

by Martin Moreno

Martin Moreno Moya

November 2025

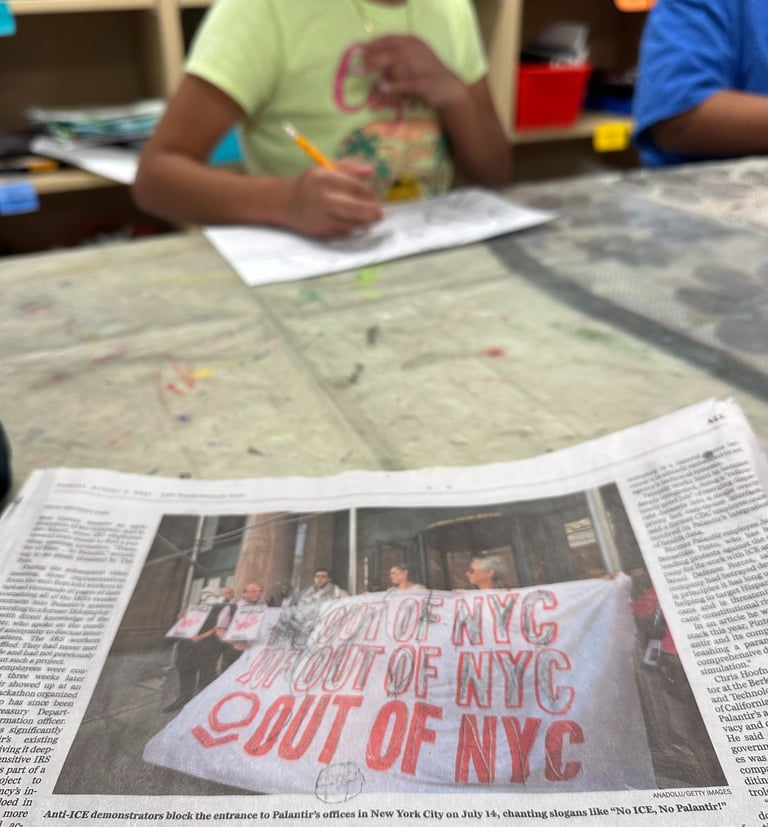

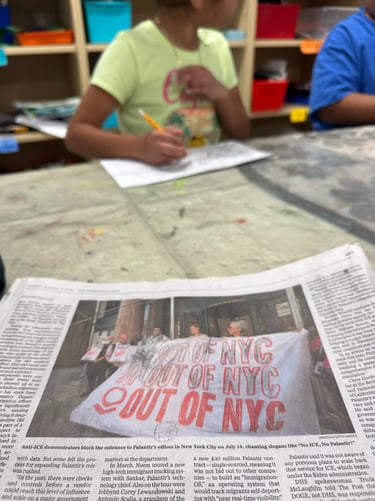

I met them on an ordinary Friday afternoon, two kids I had never seen before, sitting at a long table covered in paint and newspapers at an after-school art class. The boy was from Mexico, the girl from Guatemala. I wanted to know their stories, how they ended up here in Arlington with brushes in their hands and huge smiles on their faces. But before I could ask a single thing, they were already interrogating me with the rapid-fire curiosity only eight-year-olds have; they were more interested in me than I was in them.

“¿Ronaldo o Messi?”

“¿De dónde eres?”

They were still learning how to navigate English, so I spoke in Spanish with them. Their eyes locked onto mine at an upward angle, laughing and smiling between every question. For a moment, they were simply children, happy, playful, loud, and full of wonder.

Then the girl asked quietly:

“¿Conoces a la migra?”

I paused. “¿Qué?”

The boy then added:

“¿Y ICE?”

I froze. I gasped. I shook my head.

They were eight.

Eight years old, and already fluent in the language of fear.

In that moment, the room felt suddenly heavier. These wide-eyed children, barely tall enough to reach the table without stretching, carried inside them a gnawing terror that adults often debate casually on the news. A fear not of monsters lurking beneath the bed, but of real people in uniform jackets who have the power to erase their families from a country they already call home.

We stood together on the same soil, the soil that once welcomed immigrants who built America brick by brick, and yet these kids had already been taught that they don’t belong here. That they are a mistake. A threat. A risk to be taken care of.

What struck me the most wasn’t just that they knew the word ICE, but how they said it, in a way that didn’t sound like a question of curiosity but rather a question of pure survival, such as, Do you know the monster too? After class, when the other kids had left and I was helping them wash the paint off their hands, I asked gently if they felt safe here. They didn’t hesitate to start talking about ICE and Trump, highlighting the fear that had become a part of the vocabulary of politics they never asked to learn.

So I pressed record.

Not because I wanted attention.

Not because I wanted a story.

But because the world needs to hear what innocent Hispanic children are carrying silently on their backs every day.

Their words were heartbreaking to me and full of meaning. They reflect a bigger truth we have allowed to grow in this country: Hispanic children, many of them U.S. citizens themselves, are growing up afraid of the very government supposedly built to protect them. Their childhood is being interrupted by policy. Their innocence is being shaped by rhetoric. Their sense of belonging is being eroded by debates in which they have no voice.

This is not about partisanship. It’s about being human.

As someone who moved countries at thirteen and struggled to adapt, I can easily sense fear among immigrants like myself. But I never carried the kind that makes a child openly speak out loud about their sense of belonging, or if they have the right even to exist where they stand, long before they even understand the laws that threaten them. No eight-year-old should know the meaning of deportation.

Yet here we are.

The day I met those two kids at Cardinal Elementary School changed me. It reminded me that the darkest side of politics is the quiet harm that goes unnoticed, lying in the shadows of people’s ignorance.

Since 2020, America has been infected by not just the coronavirus but also the polarization virus that slowly divides adults and rapidly spreads to every child who is unfortunately cursed with the ability to see the world differently than we do.

Politics infiltrates a child’s mind sideways, through mood, through tension, through what their parents worry about when they think no one is listening. When leaders describe families like theirs as problems or threats, children internalize that message framed with hostility long before they know the meaning of the words.

Even if they don’t fully understand the issues, they understand the fear.

Kids absorb politics the same way they absorb language: by watching, listening, and sensing the emotional cues around them. And if we are willing to just let fear seep into the smallest voices among us, then the cost of our political climate is far greater than any election cycle.

I recorded them because someone has to listen.

And I’m writing this because someone has to care.

America can no longer call itself a nation of opportunity while its children learn the language of fear before they learn English. We owe them more than that. We owe them safety. We owe them dignity. We owe them a childhood unburdened by politics they didn’t choose nor deserve.

The question isn’t what these kids asked me.

The question is why they had to ask at all.

And that is a question we can no longer afford to ignore.

Cardinal Elementary School. Arlington, Virgnia